23 rules to run a software startup with minimum hassle

Over the last 5 years of bootstrapping, I’ve tried a lot of things, and discovered there are many ways to create hassle for yourself that wastes time and energy and distracts you from building value in your business. This is my second post on lessons learned from bootstrapping; you can subscribe to updates to this page if you want to continue following along.

Avoiding hassle is especially important for a bootstrapped company. As discussed in my previous post about the spiderweb entrepreneur, in the early stages of bootstrapping, nothing happens unless YOU do it, so it’s incredibly important to conserve your time and energy.

If you want to absolutely minimize hassle as you run your software business, you can stick to each one of these rules, which I present in no particular order:

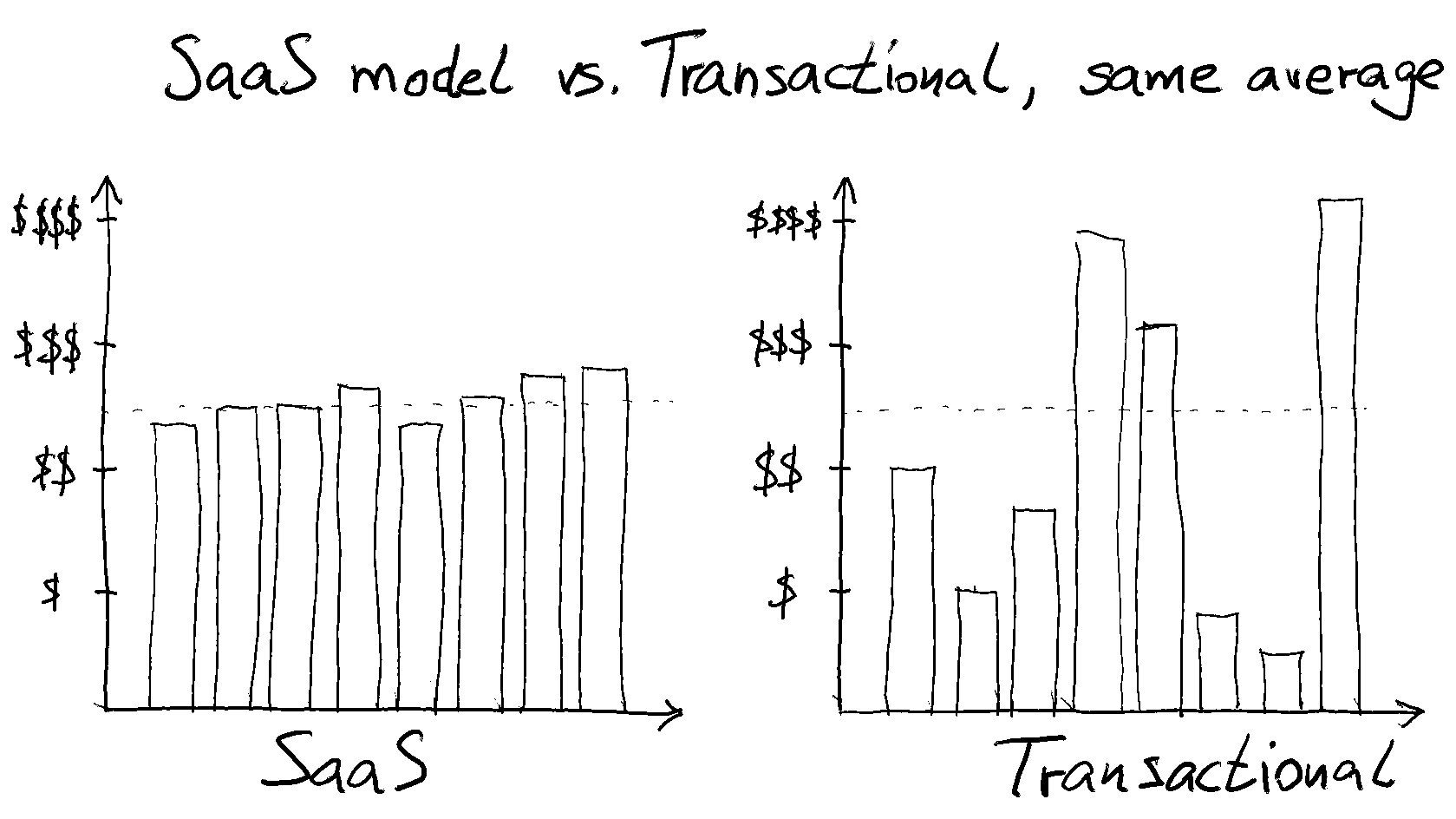

Rule #1: Recurring revenue is the way to go

If your product can be presented as a subscription, a.k.a. a SaaS product, do that. Even if you need to shoe-horn your product into that business model.

Using a SaaS model means your revenues will be predictable. In a nutshell, this month’s revenues will be your previous month’s revenues, minus folks who cancel or downgrade this month, plus those who start a subscription or upgrade this month.

Running a business with revenues that will usually grow and very rarely drop more than a little bit is about 100x less stressful than running a business where your revenues could range from a big fat zero to some huge windfall.

Rule #2: Stick everybody on a month-by-month plan

A lot of SaaS veterans will urge you to try to get subscribers to opt for annual billing up front rather than month-by-month billing, by offering a deep discount on annual plans. While this has a cash-flow advantage, it has two disadvantages:

- You get less money in total, because of the discount; and

- You erode the benefits of rule #1, as your revenues will start to be more feast-and-famine rather than almost completely predictable.

Save yourself the hassle and stick to month-by-month plans only.

Rule #3: Don’t do accounts receivable

Get your customers to pay up-front, by credit card, and using only a short list of cards that your payment processor accepts. Don’t offer payment in arrears by invoice. There is a lot of accounting hassle and time spent doing cashflow management associated with invoice billing.

Rule #4: In fact, completely outsource billing

At CrankWheel, we use the Braintree payment gateway and the Chargify subscription management platform on top of that. This is a decent solution, but if I was starting again today, I would go with Paddle or a similar software “reseller” (in name only) that takes care of everything related to billing and sales tax/value added tax and pays you a single lump sum every month. Yes they take a larger percentage than if you go straight with a payment gateway like Stripe or Braintree, but it’s a very simple way to outsource and simplify. You get:

- One lump sum every month means much simpler bookkeeping on your end;

- No customer support on your end for billing issues;

- You don’t have to fight back against chargebacks, they do that for you;

- They handle subscriptions plans, coupons, offers, dunning (retrying credit cards) and lots more.

Save yourself the hassle around billing - pay a couple of extra percentage points and be done with it.

Rule #5: Don’t do freemium

Operating a freemium model means your sales pipeline will be very long, as users typically have to build up usage over time before exceeding freemium limits, before you even have a conversation about them purchasing. This makes your feedback loop from changing things to improve conversion at various stages of the pipeline to seeing the total effect on overall conversion very long, and this makes it harder to optimize. It also will require more complex systems to track.

You’ll also end up having a lot of customer support cost related to your freemium users. I love all our users equally and we love providing excellent service to all of them, but there’s an unavoidable customer support burden from freemium that can increase your stress levels, especially when you’re bootstrapping and your team is still tiny.

Save yourself the hassle and stick with a standard, fairly short, free trial, then require payment or the account is suspended. I’d even go so far as to require the prospect’s credit card up front when starting the trial, although that is not en vogue these days. You’ll get fewer leads but they’ll be more likely to convert (stronger buying intent), which means that (a) you can spend more precious founder (or salesperson/customer success) time with them during the trial, and (b) you can bid higher for paid ads that are driving acquisition.

Rule #6: Don’t prepare for tomorrow’s success at the expense of today’s prerequisites for success

I’ve fallen into this trap myself at previous startups, making choices that are not the simplest choice for the foreseeable (short-to-medium-term) future, because I foresaw a gilded longer-term future where the best and most reasonable choices for today would not be good enough.

A typical example of this is engineering for scale too early. You (or your technical team) should choose the simplest architecture that can support your first few tens of thousands of users. Typically this will be a managed relational database, like PostgreSQL on Amazon RDS, some EC2 instances or containers and some routing on top of those, running code you develop in a single source code repository.

There is no need, early on, to develop a deployment or code architecture that will scale to support tens of millions of users and/or a development team of dozens. It will slow your progress to a crawl and make it a lot less likely that you reach break-even before your business starts taking off.

Save yourself the hassle. Keep things simple, and make the most reasonable decisions to achieve your short-term goals as quickly and efficiently as possible, with a bit of balance for your mid-term goals. Ignore your longer-term goals if it saves you time now - you can always change course later, and you’ll have more resources to do so if and when it’s needed.

Rule #7: Choose simple, boring technology

Almost by definition, the goal of building a bootstrapped startup is to create a viable business. You might have a secondary goal of learning how to do so along the way - that’s all good. But don’t also make it a goal to learn fancy new technology framework along the way, unless there is no other way to build your intended solution - that adds significant, avoidable technical risk.

Save yourself the hassle. Use a database you (or your technical team) are familiar with. Choose a programming language you understand well. Use a framework you already used. Focus the new, risky stuff in your startup on what you’re building that’s actually new.

Rule #8: Choose a stable, multi-vendor platform

If you’re dependent on a single vendor, I can almost guarantee this will be painful over time. App platforms like the Apple App Store, Google Play, and the Chrome Web Store, and e-commerce platforms like Shopify and Magento, or CMS platforms like WordPress are all examples of this.

While there can be benefits to building on a single-vendor platform such as its often built-in marketplace, it also guarantees that once every few months you will be scrambling due to some change or another that the platform vendor is enforcing, and sometimes it won’t just be a scramble to keep up, it can literally be an existential crisis for your business.

You can avoid this hassle by building on top of long-term stable, multi-vendor platforms like the web, or Linux.

Rule #9: Use a managed office

Running your own office is a hassle. Your printer breaks down, you run out of coffee, there’s a leak from a pipe, your cleaners quit, you need to find someone to water the plants while you’re away, and so forth and so on. Most of these things take only a little bit of time, but add it all up and it’s a big distraction from your actual business goals.

Instead, go for a hassle-free managed office or co-working space, where if there’s a problem you can always move easily and with short notice, and all those little things get taken care of for you.

Rule #10: Use an answering service

Answering the phone when you’re heads-down doing some coding, or writing a case study, or optimizing your paid ads, is a big distraction. It’s so much better to have 80% of your calls transformed to email messages or customer support tickets, 19% batched up during a part of your day that works well for your schedule, and that 1% of truly emergency calls routed through to ring all support team contacts.

An answering service isn’t exactly cheap, but it’s worth it. At CrankWheel we use AnswerConnect and they’re very good. Make sure to give them very explicit rules for when to pass calls through, when to take a message, and when to create support tickets.

Rule #11: Choose a big, boring bank

I started with a smaller, more nimble bank for CrankWheel, thinking I would get better service. Instead, they ended up making strategic changes where they no longer want to be servicing business customers, which has meant fewer and fewer available services - and switching banks is a huge hassle.

Choose one of the big, boring banks that you can be fairly sure will still be around in 5 years and be offering the same set of services that you depend on.

Rule #12: Choose a simple corporate structure

Do you love paperwork, calls with lawyers and accountants, and learning the intricacies of running a company in different jurisdictions? No? Then choose the absolute simplest corporate structure that you can, and let it develop over time only as it becomes absolutely necessary, so that while you’re small, you’re managing a single corporate entity in a single jurisdiction with a single bank account and so on. You get the picture.

There was a time when I considered flipping CrankWheel (an Icelandic corporation) to be a US company, or opening a subsidiary in the US. I know I saved myself a ton of hassle by not doing so, and it hasn’t made a difference so far.

Rule #13: Find an accountant who will be a long-term partner

Trust me: Switching accountants is a painful process. Do everything you can to avoid it. Finding a firm you can rely on for the next 5+ years is a lot more important than whether they are 20% more expensive than some other firm.

Rule #14: Don’t take in any investors

Investors will want a seat on the board, and very often also some special rights or preferences in your company, and once they’re on board you can’t ignore them, and you shouldn’t. They will put a lot of pressure on you to grow fast, very often faster than may be compatible with your well-being, mental health, work/life balance and ability to keep finding your work fun. This is especially true if you take in VC money; their timescales are aligned with their fund lifetimes, and they typically have only 5 years until they need you to either IPO or be acquired. Their fund structure means they aren’t (and can’t be) interested in a company that pays dividends, or building a privately-held business for the long term.

Taking in investors and becoming addicted to raising that next round of funding is also one of the most major distractions you can have from actually building value in your business. Ask any founder who’s gone through fundraising, and they will tell you it takes away all of their focus for multiple months for each round.

You can avoid this hassle by bootstrapping, self-funding, or customer-funding. It’s not all roses, but bootstrapping will act as a forcing function that uniquely aligns you with what your customers value.

Rule #15: Don’t apply for grants

A typical government grant for research and development will often require you to set a direction for 2+ years and then more or less stick to that direction, or you won’t get all the grant money. This will affect your decision-making process by creating an incentive that is not necessarily aligned with building value in your business as fast as you can. Align yourself with your customers by making them your almost-exclusive source of revenue.

I will caveat this by saying that grants that come with no strings attached (except for some after-the-fact reporting requirements), such as R&D tax refunds, are essentially free money and as long as you can spare the time to do the required reporting, you should go for these.

Rule #16: Don’t do partnerships

Any partnership will take a lot of your time, and often requires a significant investment on your end, be it a reseller, channel partner, marketplace, co-promotion or similar partnership. Often, your partner is not similarly invested in terms of money or time (in which case - definitely don’t do the partnership).

The other problem with partnerships is that they most often remove you one step away from customers. This means you learn more slowly what your customers want and need. It will be that one step harder to provide excellent customer support and build your brand.

Rule #17: No patents

For small companies, patents are unlikely to be of high value unless you hope to get acquired by one of the huge tech companies one day. Filing for patents is a fair amount of effort on your behalf, a big distraction when you’re a small team, and it costs a lot of money. There is not just the initial cost of filing but there can be several occasions where you need an additional outlay of multiple thousands of dollars to continue prosecuting the patent. Even then there’s no guarantee you it will be granted.

Let’s say you get a patent and BigCo starts infringing it. They will have 1000x more legal resources than you do, so you have no chance of suing them. Conversely, let’s say SmallCo infringes on your patent. You might have a chance but the risk you won’t win won’t be worth the legal costs.

The one situation where the patent could be worth something (apart from an acquisition) is when OtherCo tries to sue you due to infringing their patent. You can try to keep on hand well-documented prior art (with dates validated by some 3rd party) but since most jurisdictions now have a firist-to-file policy this might not help very much. You need to balance this possibility against the perceived risk of being sued.

I’ll add a standard “I am not a lawyer” disclaimer, so don’t blame me if you take my advice and I’m wrong.

You can save yourself a fair bit of hassle by not filing patents at all. Think about whether this is right for you.

Rule #18: No acquisition talks

Once you have a successful business and have built a bit of a brand, various people might approach you asking if your company is for sale.

If you want to stay focused on building value in your company, skip all such talks. A simple response saying you’re not interested is all it takes.

Rule #19: Don’t use every marketing channel

If you try to market via too many different channels, with a small team, you’ll do all of them poorly. Pick a couple at a time and get excellent at them, or learn early that something doesn’t work for your product, and move on to a new channel.

For the channels that work, systematize as soon as you can. This allows you to up the volume on those channels sooner. Alternatively, it lets you decrease the time commitment you need to run the channel.

For example, say content marketing is a channel that looks like it’s working. You can create standard operating procedures and have your VA do more of the work. Then you can up the frequency of blog posts from once every two weeks to once per week (see more on this subject in my post on the spiderweb entrepreneur).

Rule #20: Invest in marketing rather than spending on marketing

If you can find a marketing channel that rewards product quality and investment over time, prioritize that channel.

Examples of such channels would be app store listings, software directories, and similar marketplaces. You can invest in these by asking your users for reviews. Remember to build a great product so your reviews are good.

Another example is content marketing, where you can invest in SEO to bring free traffic to your site. Yet another is affiliate marketing, where you can invest in recruiting and training your affiliates.

Over time, these types of investments in marketing will bring in compounding amounts of business.

Rule #21: Don’t do big launches

A “big launch” such as organizing a launch event at a conference, or finding somebody prominent on Product Hunt to hunt your product, or similar “all or nothing” launches are a huge distractions over several weeks to everything else you should be doing in your business. They also might not help you prove out your business case and find your ideal target customers, as the profile of users signing up in big launches like these is likely to be different from the profile of users you are able to attract through your ongoing marketing activities.

A big launch is also the ultimate example of spending on marketing rather than investing in marketing. You might say it’s an investment because it lets you build up a list of beta testers or users. The truth is, it’s more like “investing” in a car, because it depreciates pretty quickly. A couple of years down the line, you might have only 10% of those early users remaining on your beta tester list, and nothing else to show for your tremendous effort.

Save yourself the hassle and skip the big launches. Invest in your repeatable, scalable, compounding marketing channels instead.

Rule #22: Don’t do trade shows/conferences

Trade shows and conferences are very expensive, and they are a tremendous distraction for a tiny bootstrapped team. Several weeks before the event, someone on the team starts spending part of their time booking furniture, creating marketing materials, doing social media outreach, etc. The last week before the show, it’s all about outreach to warm up leads at the show. The week of the show, you get nothing done except travelling to and attending the show and just barely keep up with email. At least one week after and often many, you’re all going at a crazy pace working through leads from the show, and unless you went to a very targeted show, those leads are more likely unqualified than not.

Save yourself the hassle and the money, and go with the marketing channels you can invest in instead.

Rule #23: Don’t respond to anything unsolicited

As soon as your startup has an online presence, you will start getting all kinds of unsolicited emails and phone calls. Everyone and their uncle wants to offer services and products to your company.

Ignore all such contact. As a startup founder and leader of your team, you need to manage your own and your team’s time and priorities yourself, based on what’s the most reasonable next investment at any given time. Don’t be swayed by unsolicited proposals. At best, you can file away the unsolicited emails as potential providers down the line. You decide when it’s time you need a particular product or service.

A confession, and a caveat

I’ve broken almost every one of the rules above!

Not only that, I continue to break many of them on a regular basis, when I decide it makes sense for my business. CrankWheel has fantastic partners, we do lots of conferences, we accept annual payments and invoice billing, we’re a freemium product fairly reliant on one vendor’s marketplace (the Chrome Web Store) and we dabble in more marketing channels than maybe we should. In the past, we’ve taken grants, done big launches, and more.

The rules are not meant as absolute rules, but as food for thought: For you to think about the tradeoffs, of how and why there will be additional hassle and distraction from your core activities, if you decide to “break” one of the “rules”.

For example, if you decide going to trade shows is right for your business, you should understand the fully-loaded cost of doing that. Not just the cost in money but also the cost in time. Depending on your product, they can still be one of the absolute best ways to reach your ideal customers.

As another example, you might decide that the type of business you’re running can only be successful if you take in VC money. You need to be aware of the tradeoffs of working with institutional investors, but it’s a given that there are certain types of businesses that are more likely to be successful with investment than without.

I could go on and on, but as a final example, if you think you will ever want to sell your company, the right time to do so is when you have inbound interest, so go ahead and smash that rule. Your valuation will be higher when there is inbound interest from multiple parties, than if you later try to initiate acquisition discussions.

Now go forth and break the rules - but not without thinking.

Snapshot of older comments

I was using a plug-in called Disqus for comments, but it recently went crazy with spam ads from around the web, so until I get around to switching to a different commenting system, here’s a static snapshot of previous comments on this post